Philip Arthur Larkin

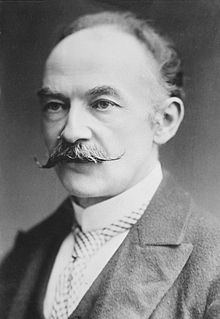

, CH, CBE, FRSL (9 August 1922 – 2 December 1985) was an English poet and novelist. His first book of poetry, The North Ship, was published in 1945, followed by two novels, Jill (1946) and A Girl in Winter (1947), and he came to prominence in 1955 with the publication of his second collection of poems, The Less Deceived, followed by The Whitsun Weddings (1964) and High Windows (1974). He contributed to The Daily Telegraph as its jazz critic from 1961 to 1971, articles gathered together in All What Jazz: A Record Diary 1961–71 (1985), and he edited The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse (1973).He was the recipient of many honours, including the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry. He was offered, but declined, the position of poet laureate in 1984, following the death of John Betjeman.

After graduating from Oxford in 1943 with a first in English language and literature, Larkin became a librarian. It was during the thirty years he served as university librarian at the Brynmor Jones Library at the University of Hull that he produced the greater part of his published work. His poems are marked by what Andrew Motion calls a very English, glum accuracy about emotions, places, and relationships, and what Donald Davie described as lowered sights and diminished expectations. Eric Homberger called him "the saddest heart in the post-war supermarket"—Larkin himself said that deprivation for him was what daffodils were for Wordsworth.Influenced by W. H. Auden, W. B. Yeats, and Thomas Hardy, his poems are highly structured but flexible verse forms. They were described by Jean Hartley, the ex-wife of Larkin's publisher George Hartley (The Marvell Press), as a "piquant mixture of lyricism and discontent", though anthologist Keith Tuma writes that there is more to Larkin's work than its reputation for dour pessimism suggests.

Larkin's public persona was that of the no-nonsense, solitary Englishman who disliked fame and had no patience for the trappings of the public literary life. The posthumous publication by Anthony Thwaite in 1992 of his letters triggered controversy about his personal life and political views, described by John Banville as hair-raising, but also in places hilarious. Lisa Jardine called him a "casual, habitual racist, and an easy misogynist", but the academic John Osborne argued in 2008 that "the worst that anyone has discovered about Larkin are some crass letters and a taste for porn softer than what passes for mainstream entertainment". Despite the controversy Larkin was chosen in a 2003 Poetry Book Society survey, almost two decades after his death, as Britain's best-loved poet of the previous 50 years, and in 2008 The Times named him Britain's greatest post-war writer.

In 1973 a Coventry Evening Telegraph reviewer referred to Larkin as "the bard of Coventry", but in 2010, 25 years after his death, it was Larkin's adopted home city, Kingston upon Hull, that commemorated him with the Larkin 25 Festival which culminated in the unveiling of a statue of Larkin by Martin Jennings on 2 December 2010, the 25th anniversary of his death.

, CH, CBE, FRSL (9 August 1922 – 2 December 1985) was an English poet and novelist. His first book of poetry, The North Ship, was published in 1945, followed by two novels, Jill (1946) and A Girl in Winter (1947), and he came to prominence in 1955 with the publication of his second collection of poems, The Less Deceived, followed by The Whitsun Weddings (1964) and High Windows (1974). He contributed to The Daily Telegraph as its jazz critic from 1961 to 1971, articles gathered together in All What Jazz: A Record Diary 1961–71 (1985), and he edited The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse (1973).He was the recipient of many honours, including the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry. He was offered, but declined, the position of poet laureate in 1984, following the death of John Betjeman.

After graduating from Oxford in 1943 with a first in English language and literature, Larkin became a librarian. It was during the thirty years he served as university librarian at the Brynmor Jones Library at the University of Hull that he produced the greater part of his published work. His poems are marked by what Andrew Motion calls a very English, glum accuracy about emotions, places, and relationships, and what Donald Davie described as lowered sights and diminished expectations. Eric Homberger called him "the saddest heart in the post-war supermarket"—Larkin himself said that deprivation for him was what daffodils were for Wordsworth.Influenced by W. H. Auden, W. B. Yeats, and Thomas Hardy, his poems are highly structured but flexible verse forms. They were described by Jean Hartley, the ex-wife of Larkin's publisher George Hartley (The Marvell Press), as a "piquant mixture of lyricism and discontent", though anthologist Keith Tuma writes that there is more to Larkin's work than its reputation for dour pessimism suggests.

Larkin's public persona was that of the no-nonsense, solitary Englishman who disliked fame and had no patience for the trappings of the public literary life. The posthumous publication by Anthony Thwaite in 1992 of his letters triggered controversy about his personal life and political views, described by John Banville as hair-raising, but also in places hilarious. Lisa Jardine called him a "casual, habitual racist, and an easy misogynist", but the academic John Osborne argued in 2008 that "the worst that anyone has discovered about Larkin are some crass letters and a taste for porn softer than what passes for mainstream entertainment". Despite the controversy Larkin was chosen in a 2003 Poetry Book Society survey, almost two decades after his death, as Britain's best-loved poet of the previous 50 years, and in 2008 The Times named him Britain's greatest post-war writer.

In 1973 a Coventry Evening Telegraph reviewer referred to Larkin as "the bard of Coventry", but in 2010, 25 years after his death, it was Larkin's adopted home city, Kingston upon Hull, that commemorated him with the Larkin 25 Festival which culminated in the unveiling of a statue of Larkin by Martin Jennings on 2 December 2010, the 25th anniversary of his death.

Poetry

Main article: List of poems by Philip Larkin

- The North Ship, The Fortune Press, 1945, ISBN 978-0-571-10503-8

- XX Poems, Privately Printed, 1951

- The Less Deceived, The Marvell Press, 1955, ISBN 978-0-900533-06-8

- "Church Going"

- "Toads"

- "Maiden Name"

- "Born Yesterday" (written for the birth of Sally Amis)

- "Lines on a Young Lady's Autograph Album"

- The Whitsun Weddings, Faber and Faber, 1964, ISBN 978-0-571-09710-4

- "The Whitsun Weddings"

- "An Arundel Tomb"

- "A Study of Reading Habits"

- "Home is So Sad"

- "Mr Bleaney"

- High Windows, Faber and Faber, 1974, ISBN 978-0-571-11451-1

- "This Be The Verse"

- "Annus Mirabilis"

- "The Explosion"

- "The Building"

- "High Windows"

- Thwaite, Anthony, ed. (1988), Collected Poems, Faber and Faber, ISBN 0-571-15386-0

- "Aubade" (first published 1977)

- "Party Politics" (last published poem)

- "The Dance" (unfinished & unpublished)

- "Love Again" (unpublished)